What is a tribal rug? I am asked this question frequently. There is a simple answer… but also a more nuanced answer so I will try to give you both.

First off, my website is broken into several “Search By Style” categories including “Tribal Designs“. This is somewhat of a broad category and sometimes it is hard to know exactly how to categorize a particular rug. In short, tribal rugs are rugs that were woven by nomadic or semi-nomadic tribal weavers. The tribal people most often associated with weaving rugs are the Turkmen, the Belouch, the Kurds, the Qashqai to name just a few. Tribal rugs are recognizable by their more geometric motifs as opposed to the curvilinear and floral motifs of city rugs.

But, this is too simple an answer. There is more to this question. It is widely believed that the art and craft of the hand knotted carpet began with the pastoral nomads of Central Asia. These nomadic people had a ready supply of wool from their sheep. The first carpets were probably simple animal pelts. But, at some early point of human development, weaving was invented. Certainly, there was some benefit to weaving coverings from cut wool. It is believed that the first knotted pile carpets perhaps resembled animal pelts with long pile shag. Much like today’s Turkish tulu rugs, these early woven “pelt” rugs were warm coverings and bedding.

Although wool is used to create felts for tents and flat woven textiles throughout Central Asia, it is only the more western tribes that appeared to develop the more complex knotted pile technique. The Mongols of the east (although very similar) never used the knotted pile weave as opposed to neighbors to the west; Kirghiz, Kazakh and Turkmen.

Sadly, there is little archeological material uncovered to aid much in uncovering the history of the knotted pile rug. For this reason, much is open to speculation and informed guess work. However, the theory is that it is the nomad tribes that first mastered the knotted pile technique and latter this sophisticated technique spread over the centuries. The oldest know carpet ever found (the Pazyryk carpet) is less than 3000 years old. However, the incredible artistry and workmanship of this carpet suggests the technique of knotted pile had already progressed for centuries before the creation of this textile. In any event, this rug was found in a burial tomb of Siberia where this form of weaving is thought to have begun. And interestingly, the life-style of these early steppe nomads is very similar to the few present-day steppe dwellers such as the few Kazakh, Kirghiz, Uzbek and Turkmen who still live a more traditional lifestyle.

Apart from this, not much is know about tribal weaving until the 18th and 19th centuries. The term “tribal” is used somewhat loosely. Originally, tribal rugs came exclusively from the nomadic tribes. Starting my business, I was so influenced by the creativity of these tribal textiles that I named my business “Nomad Rugs”. The truth, however, is that many tribes who used to be nomads had settled into villages centuries ago. And other tribes lived “semi-nomadic” lives, wintering in villages and spending summers in mountain pastures with their flocks.

Another aspect to tribal rugs (which might more aptly be called tribal-style rugs) is that the earlier examples were woven private use. These rugs were not being woven or influenced by market forces or exporters specifications. The designs and color combinations were truly indigenous inspirations. The design origins and meanings are shrouded in mystery too. In some rugs there are clearly zoomorphic designs and motifs that clearly inspired by plants and flowers. But many designs are wildly abstract. Some motifs are know to impart talismanic and protective qualities. And many designs have multiple meanings and names ascribed to them. One thing that is clear is that tribal design in hand knotted rugs are not hieroglyphics with specific literal meanings. But the power and majesty of great tribal rugs, like all great art, certainly convey meaning; and perhaps even multiple layers of meaning.

Tribal style weavings have a strong local tradition with traditional and perhaps heraldic motifs and designs that change little over centuries. Traditional design and color was passed down from mother to daughter. And since these rugs were not meant for the commercial trade, the identity of the weaving group and the personal pride of the weavers family was expressed in the objects of personal expression. Each different tribe had exclusive designs and color combinations. Among Turkmen weaving, one can also notice how larger tribes would subsume the smaller tribes and end up appropriating design elements. The language of the tribal rug is a varied and rich visual language.

Much of the appeal of tribal style designs is the intricate receptive nature of most design motifs. Whereas the complex designs of formal carpets are graphed onto paper so that weavers could replicate the intricate motifs. However, tribal style rugs are often comprised of several repeating motifs and are repeated over a field in various permutations and color combinations. As such, tribal weavers were able to memorize the motifs that made up their tribes visual nomenclature. And they were able to produce their rugs without the aid of graphs of samplers. And in many if the more playful examples of tribal rugs, one can see how a weaver may improvise and play with a design element or layout. Individuality was expressed in small ways. The overall design scheme and color combinations of tribal rugs is fairly consistent but within this consistent form, one can spot many unique and personal improvisations.

By the 18th and 19th century, many nomadic tribes were seen as a threat to the rulers of the countries or kingdoms which they occupied. After all, grazing sheep have no notion of territory or boarders. And to the nomadic tribes, these distinctions were equally unimportant. But how can you rule a people who freely cross from one territory to another? As such, many tribes were forced to settle or to remain in localized areas. One of the most violent settlements was the defeat of the Tekke Turkmen tribesmen by the Czarist Russian army in 1881. These fiercely independent Turkmen were decimated after decades of conflict. Many fled to Afghanistan or Persia and those who remained were forced to settle. At this time, many of their carpets which had been prized possessions were sold off and shipped off to the European cities of Moscow or St. Petersburg by way of the Central Aisan trading capital of Bukhara. These carpets were named, Bukharas, by the carpet merchants and they have since been copied in cheaper mass produced version in Pakistan. The Pakistani “Bokhara” carpet, is actually a cheaper reproduction of the classic Tekke Turkman “main” carpet.

The 1860s saw the development of the first synthetic dyes. These early aniline dyes proved to be terrible. They faded rapidly in the sun, they ran when washed with water and they had garish and overly bright hues. However, their ease of use meant that they had soon supplanted the beautiful natural dyes that had previously been used by all tribal weavers. Many think that the introduction of synthetic dyes spelled the end of “authentic” tribal weavings but this is only partially true. It was certainly also a victim of the machine age and the forced settlement of previously nomadic peoples. These people began to weave rugs more for market export rather than personal and tribal identity. So design were mutated and changed and morphed into second rate copies of the fine textiles that had come before. In some areas, the decline happened more rapidly than in others. In some remote pockets, tribal weavers continued to create authentic tribal weavings.

This leads to the difficult question of what is an authentic tribal style rug. Is it a rug that is exclusively made with all natural dyes. Is it a rug that predates a certain era of forced settlement or influence from western markets. Or is it a rug that maintains a certain level of design integrity? I will leave the debate to the scholars. I believe that each individual rug should be judged on its own merits.

The 1980s saw the raise of the natural dye renaissance in hand knotted rugs. For decades, the older pre-synthetic dyed rugs were prized for the colors. And the newer rugs being made with synthetic could not compare to the classics. But, rug producers started experimenting successfully with reviving the natural dye recipes to unlock the secrets of these radiant colors. These rug producers were not only interested in great color but they were also interested in great design.

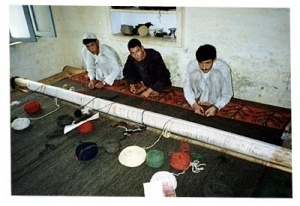

These early pioneers in the vegetal dye renaissance looked to the classic tribal weavings on the 18th and 19th centuries for inspiration. One such person was Chris Walter with his Ersari Cultural Revival project. Chris Walter (an American rug importer and producer) teamed up with Jora Agha, an Ersari Turkman, in Northern Pakistan in 1987. Jora had previously fled the Russian invasion of Afghanistan with his family. Chris Walter, who was exporting carpets from Pakistan at this time, saw the Turkmen weavers in the camp weaving carpets in inferior machine spun wool dyed with natural dyes. He had the idea of providing these weavers with fine handspun and naturally dyed wool. These superior materials were requisitioned to produce carpets that paid homage to the rich weaving tradition of the Ersari Turkmen weavers. So with the partnership of Jora to oversee weaving and production, Chris and Jora started producing new rugs with classic 18th and 19th century Ersari Turkmen designs. These are some of my all time favorite rugs and for many years I have owned one myself that is prominently displayed in my living room.

These early pioneers in the vegetal dye renaissance looked to the classic tribal weavings on the 18th and 19th centuries for inspiration. One such person was Chris Walter with his Ersari Cultural Revival project. Chris Walter (an American rug importer and producer) teamed up with Jora Agha, an Ersari Turkman, in Northern Pakistan in 1987. Jora had previously fled the Russian invasion of Afghanistan with his family. Chris Walter, who was exporting carpets from Pakistan at this time, saw the Turkmen weavers in the camp weaving carpets in inferior machine spun wool dyed with natural dyes. He had the idea of providing these weavers with fine handspun and naturally dyed wool. These superior materials were requisitioned to produce carpets that paid homage to the rich weaving tradition of the Ersari Turkmen weavers. So with the partnership of Jora to oversee weaving and production, Chris and Jora started producing new rugs with classic 18th and 19th century Ersari Turkmen designs. These are some of my all time favorite rugs and for many years I have owned one myself that is prominently displayed in my living room.

Other producers and exporters have experimented with similar ideas faithfully recreating wonderful Belouch rugs, Kurdish designs, countless Caucasian design and recently there has been a lot of interest in creating quality rugs with antique North African tribal designs. And in further explorations, producers have experimented in using non-carpet textile sources to create new carpet designs. So we have Kaitag embroidery rugs, Ikat rugs, Suzani rugs, Uzbek embroidery rugs and others! These new rugs are such masterpieces that we like to boast that these are “new rugs that antique tribal rug collectors like to own”! This boastful claim is actually true as I have sold many of our new rugs to antique rug collectors!

Thanks for reading this too brief foray into the wonders of tribal style rugs inspired by the nomadic artisans. If in the Bay Area, please stop by our San Francisco showroom to check out some of these wonderful rugs that being made today. And don’t take these rugs for granted! Fewer and fewer people are interested in weaving rugs today. Younger generations in Persia, Turkey, India, Afghanistan and elsewhere are no longer going into the skilled craft of weaving. Perhaps in 20 years from now, hand woven rugs will be as scarce as the ill fated dodo bird? In any event, it is an honor to be able to sell these incredible rugs today!

best,

Chris, owner Nomad Rugs, San Francisco

© 2026 Nomad Rugs. All Rights Reserved.

© 2026 Nomad Rugs. All Rights Reserved.

Great and thorough explanation. You have a beautiful collection of rugs.

Thank you! Much appreciated!

I so thoroughly enjoyed reading this! I inherited a lovely area rug with what I believed to be seagulls on it and have been researching ever since. I found more inormation in this ‘brief foray’ than in any other reading I’ve done! Thank you. Your rugs are beautiful. Teresa

Hi, I have a rug 17’x6′ I believe silk with the year in a persian old fashion 1911 also persian characters on the far right side weaved into the most beautiful rug. I have no idea of the true age and I am most interested in this is a tribal rug with the family name weaved into rug.

Greetings. Please send a photo to [email protected] and I will try to identify the rug for you. Best regards, Chris

Hi. Are you still in business? Wonderful informative article.

Yes! We are open daily in our San Francisco store and online too. thanks, Chris

Hi Chris ! I have some Turkish wool rugs . I would like to know how much do they worth. If it’s ok I would like to send you some pictures . Thanks.

You are welcome to email me pictures although I am not an expert on antique rugs. thanks, Chris

I have a beautiful six gul chuvel unique.

To Today, I have not seen another like it in description. One may say I’m a novice , but I have a vast library of research and family history in the field and i am still at alost.

I have not seen a piece similar in description or quality. Personally I have a large private collection of tribal weaving.

Your paper on Tribals Weaving is very enlightening. I feel you may offer insight.

The six solar guls chuvel In my possession may sound typical ,but Strangely different from everything I’ve ever seen . The second row guls has pair of lighting bolt on the side of each sular gul. the second row guls are slightly bigger Due to the this fact.

I can describe this example as being wedding weave in quality , but strangely all the white is carved out. The area carved are Measured in less than centimeter. I stress again everywhere that is white carved out. The minor guls look to be Tukke.

There’s so many other aspects of this piece I could try to described but I do not have the words.

If you’re interested let me know I’ll post you a picture of this piece.

Sincerely Mr. Holmes

You are welcome to send me images and I will gladly take a look although I am not an expert in antique Turkman weaving. Your might look up Turkotek for some more expert advice. thanks, Chris

Good article. I have two tribal rugs. I looked this up because I am going to take the big one, a kilim, to school tomorrow and have my 7th graders sit on it on the grass while I teach them math. We’ve had some covid, so we’re holding our classes outside. I’ll tell them that nomad rugs were meant to be carried around and used like that, which is what the local Bloomington Afghan rugseller said to me last year. He had his shop closed except by appointment and told me he hadn’t sold a rug for 4 months, because of covid.

Question: Are most “tribal” rugs now made in large establishments using tribal designs, or are they mostly by single families living in villages (I don’t suppose many are really nomadic any more). If by single families, how many rugs would a family make in one year?

What a lovely way to teach a class! Great way to adapt in these times! I really appreciate your work and the work of all educators! You are forming our future adults! best regards, Chris

Oh, and in reply to your comment there are very few tribal rugs today that are made by nomadic weavers. Modern life has eradicated the nomadic life for most tribal groups. There are still some people that are “semi-nomadic” where they spend winters in villages and summers in the mountain pastures with there herds. Most tribal rugs we sell are made by people who are living in villages. For example, many of our rugs come from Ersari Turkman weavers working in Northern Afghanistan. They weave some of their traditional and ancestral designs. But they also weave designs that we commission from other sources. And I do not know how many rugs are made by most families.