Every moment and place says,“Put this design in your carpet!” Rumi

The Carpet as Expanded Consciousness

The aim of this discussion is to cultivate the idea that handmade carpets are portals of expanded consciousness. I will posit the idea that the design and the manufacture of handmade carpets (from the Middle East and central Asia) woven in a traditional setting draw from the experience of expanded states and open towards these states. Whether those states are induced by plant medicine, dream, song, trance or the flow state.

Humans have a very ancient tradition involving the use of mind altering experiences to produce profound spiritual and culturally edifying interior space. A cross cultural survey of ethnographic literature reveals that a large majority (more than 90% of the groups in the Middle East and central Asia) institutionalized altered states of consciousness at one point. These expanded states are given expression in the art of the carpet.

Expanded states may be entered spontaneously but also through group ritual, dance, prayer and plant medicine. One prominent example is Soma. Soma in India and Haoma in Persia is written of as both a plant and a god.

Translated from the Reg Veda

We have drunk the soma; we have become immortal; we have gone to the light; we have found the gods.

What can hostility do to us now, and what the malice of a mortal, o immortal one?

And at the same time period, Haoma was written of in the sacred Zoroastrian text Avesta as the king of healing herbs.

Though archeological evidence is still being uncovered, there is still much debate as to what exactly comprised this drink. I will not weigh in on this debate but I will point you this these fascinating videos done of Haoma this of Soma and this one also on Soma showing just several different opinions. But it is clear that soma/haoma played an important roll in Hinduism and Zoroastrianism and these religions have deeply shaped the modern world.

Interestingly, a relatively recent discovery in the heart of modern day Turkmenistan, at a site called Gonur Tepe shows archeological evidence to bolster more research into Haoma. Perhaps through cultural dissemination, this Hoama drink along with the ritual use and practices spread out into Yazd Persia of the Zoroasters as well as Vedic India. It is a thought that Haoma and Soma are the same substance of the proto Indo/Iranian tribes, which separated into Vedas and Mazda teachings respectively.

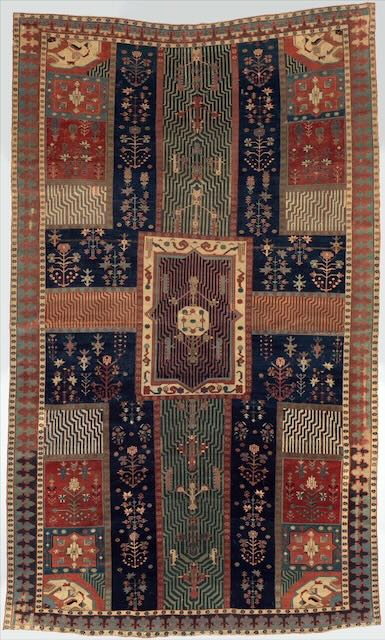

Others argue that soma/hoama are descriptions of inner states and inner alchemy. It is with this backdrop in mind that we can look at the development of weaving as an invaluable form of expression. Does the carpet depict or create the space in which to encounter the expanded state? First, I will talk of the Persian garden carpet (or the garden of Paradise) and next I will discuss the medallion carpet as a cosmic mandala. After which I will discuss the act of weaving as an act of connecting with expanded states in and of itself. As Rumi writes “let the beauty we love be what we do”.

The garden carpet depicts paradise. The word paradise entered into Latin and Greek from an old Iranian form “pairi-daêza”meaning walled enclosure.

This is because the ancient Iranian rulers built elaborate gardens with multiple plots and intricate waterways that were surrounded by walls. These elaborate walled gardens were meant to be a microcosm of the macrocosm. A garden that is all life. And later our word “paradise”.

The French philosopher, Michelle Foucault, wrote about Persian carpets and the replication of sacred space in this powerful way.

We must not forget that in the Orient the garden, an astonishing creation that is now 1000 years old, had very deep and seemingly superimposed meanings. The traditional garden of the Persian was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world with a space still more sacred than the others that were like in umbilicus, the naval of the world at its center (the basin and water fountain would be located there); and all the vegetation of the garden was supposed to come together in this space, in the sort of microcosm. As for carpets they were originally reproductions of gardens (the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to an act its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space). The garden is the smallest parcel of the world, and then it is the totality of the world.

This is an extremely useful way to look at great carpets in a unique context. They are not mere decorative objects but sacred spaces. They are not symbols pointing towards meaning but they are portals of expanded experience. As above so below. Many (perhaps most) rugs can be seen as gardens or “paradise”.

Additionally, carpets form a connection to the body, but from underneath, and therefore with some distance from mind. Despite their ubiquity, they are liminal in terms of their presence. They occupy a liminal space between nature and culture. It is also important to note that in the material culture of the tribal people of Central Asia, there was no hard distinction between the self and the culture. The various nomads of the steep who dwell in yurts with their carpet and woven textile and interiors regularly produce rugs, tents, and clothing for their needs; much of it in highly decorative patterns. There is a little material distinction between what one wore on the body and what one slept on and what one dwelled in. In the Extended Phenotype evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins makes the remarkable observation: “A beaver’s damn is the outward expression of the beaver’s genome.” One might make a similar claim of the traditional yurt dwellers of Central Asia. The body is blended as one with material culture. The chasm between the people of the yurt and the art admirers of the West is immense. We have trouble understanding and inhabiting this perspective. But the carpet in Asia was received as holding multi ancestral and communitarian memories within a perspective of singularity. The body is blended as one within material culture in identity, expression and meaning.

Furthermore, I believe that the classical medallion carpet which is more often associated with the weaving of the courts can be seen as a mandala that can orient us in life. These medallion carpets were likely originally woven in formal workshops and are less common in the tribal rugs of nomadic people. The Mamluk carpets of the 13th through 16th century are arguably the most sublime example of this type of carpet. They are mostly characterized by a central medallion, surrounded by a variety of smaller geometric motifs, forming a kaleidoscope appearance. The pallet is limited to red, blue, green and yellow tones. These carpets are both incredibly complex and mysteriously peaceful. They beckon the viewer to contemplate and enter the cosmic mandala of the medallion. In various traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation and trance induction. It is well documented that Carl Jung drew mandalas as a practice of inner work. He said that the Mandela helped him to discover and understand his inner self, and he used mandalas to heal his patients as well. The path that a mandala describes is like the circular dance of a dervish in a monastery. A mystical perspective could view these carpets as lessons that all of reality is illusory and paradoxically that the universe has an underlying structure. These medallion carpets can certainly be directly experienced through active imagination and contemplation.

On a side note, Sigmund Freud was also famously a well-known carpet collector who relished the collection he had and spent many hours contemplating the intricate designs in his collection. I believe he intuitively grasped the deeper dimension waiting to be uncovered when be asks patients what they saw when they gazed into the patterns on display. And finally, Sufi’s have been said to suggest using carpets as guides to contemplation:

One should gaze upon this object with one’s physical eyes and not move one’s eyelids to blink. One should also focus one’s inner concentration, through that object, upon the absolute reality that is essential and unchanging. One should persist with this until selfish thoughts cease, and one is overwhelmed with un-self-consciousness and one is oblivious to all things, even to the fact that one is oblivious.

Finally, I will briefly speak of the act of creating a carpet. This in itself is a meditative act. Here is a description from PD Ospensky (“In Search of the Miraculous”) relating the tribal way of life.

He spoke of the ancient customs connected with carpet making in certain parts of Asia; of a whole village working together at one carpet; winter evenings, with all the villagers, young and old, gather together in one large building and dividing into groups, sit or stand on the floor in an order previously known and determined by tradition. Each group then begins its own work. Some pick stones and splinters out of the wool. Others beat out the wool with sticks. A third group combs the wool. The fourth spins. The fifth dyes the wool. The sixth and maybe the 26th weaves the actual carpet. Men, women and children, old men and old women all have their own traditional work. And all the work is done to the accompaniment of music and singing. The women spinners with spindles in their hands, dance a special dance as they work, and all the movements of all the people engaged in different work are like one movement and one of the same rhythm. Moreover each locality has its own special tune, its own special songs and dances, connected with carpet making from time immemorial.

Finally, I can relate a conversation I recently had with a Turkish woman of Central Asian heritage who grew up in a home with her mother, grandmother and aunt’s weaving rugs. She spoke about the rhythm of the weaving, a constant beat and humming. She watched as her elders entered a trance state and got into the flow of creation. She related how when they were weaving there was never any discord or disagreement. There was peace and happiness that filled the room in a spirit that was infectious. There could be some light chatting and some laughing, but mostly just the consistent base note of weaving fingers on warp threads and the pounding of combs. She related how this space connected these weavers with all the weavers in their lineage. In this space, tradition and lineage appeared. A state that included all the generations that had come before them that had passed on the designs. As well as the hopes and love for the generations who would inherit the carpet in the future. The designs were not discussed or debated. They simply flowed from the weavers fingers in a cosmic conversation reaching back and forward in time.

I will furthermore add that in my estimation, you can feel the weavers presence in a good rug. You feel their spirit, feel their intention you feel their attention. Weaving a carpet is highly complicated and technically difficult. It’s impossible to be on auto pilot when weaving as the colors are constantly changing based on the design. It requires a very high state of attention while also a state of suspending ones thinking. To me this is one of the reasons that good carpets have a strong feeling to them that are transmitted through time; an energy that is transmitted from one human to the other through the intermediary of material culture and the sacred space that is the hand woven carpet.

This essay is highly speculative and mostly fueled by trying to elucidate some of the magic and mystery I feel in carpets. Have you ever felt a sense of expansion when in the presence of a great rug? I would love to hear your thoughts.

Thanks for reading!

Chris, Nomad Rugs

© 2026 Nomad Rugs. All Rights Reserved.

© 2026 Nomad Rugs. All Rights Reserved.

I loved it !!! I learned so many new things with your writings. I can feel in your words your love for rugs and the Peoples that made and make them. And those rugs in the pictures are beautiful and so captivating, I could be looking at them for hours. They do definitely are portals to the cosmic realm, sacred tools for experiencing altered states of consciousness. So very powerful. I’m so happy you “let the beauty You love be what You do”!! 🙂

Besos,

Lorena

Many thanks!!! So appreciate it!

Chris